December has kicked off HIP HOP 50, its multiyear, cross-platform programming initiative celebrating the 50th anniversary of Hip Hop in collaboration with entertainment company Mass Appeal. The first release of HIP HOP 50 is You’re Watching Video Music Box, a documentary that chronicles the longest-running music vide show in the world, Video Music Box. The film is directed by Emmy and Grammy Award-winning music legend and Mass Appeal partner Nasir “Nas” Jones.

The documentary gives a look into visionary DJ and MC Ralph McDaniels and the show that has become a Hip Hop mainstay since its 1983 launch. Uncle Ralph serves as a leading Hip Hop influencer, tastemaker and documentarian, showcasing and debuting Hip Hop videos and introducing viewers to future stars like Nas, Jay Z, LL Cool J, Nicki Minaj, and Fat Joe long before they were icons of the genre.

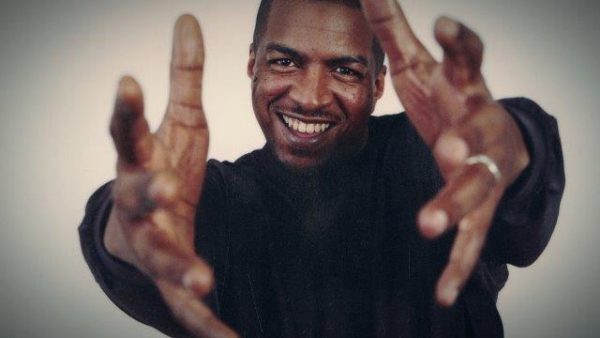

Speaking with The Source, Ralph McDaniels affectionately referred to as Uncle Ralph, reflected on the creation of Video Music Box and the impact it had on Hip-Hop for the last couple of decades.

Video Music Box was one of the first platforms that provided a route for Hip-Hop music. Looking back, how does it feel to be intricate to the success and development of the genre over these last almost 50 years?

Ralph McDaniels: It doesn’t even seem like almost 50 years. It seems like we just started, so there’s so much to do in hip hop and documentaries. You know, You’re Watching Video Music Box is an educational aspect of what hip hop is all about. It’s super important. So we still have a long way to go, but I mean it’s humbling. It’s humbling to watch. So yeah, so this is pretty awesome.

You have some iconic rap moments in the stash. What let you know that this documentary was the proper time to let them out?

For me, Video Music Box, it’s the legacy. As you get older in hip hop, you start thinking about not being missed in the conversation. So let’s start to put some of this stuff out. For people that really follow the show, they’ve been aware of it, but the rest of the world doesn’t know as much. So we just felt it was the right time. We’d been working on this project for almost like three, four years now. And I’m glad that it dropped.

You worked with Nas on this and you helped introduce him to the world. So in a way, this is kind of like a full-circle moment. How was it connected with him for this documentary and how did you combine both of your creative geniuses to tell a story?

I think spiritually we’re in the same place. He’s a guy that I first met in ’94 and there are not too many artists that you keep in contact with over the years. For him to tell me that he wanted to direct this was very humbling because with the extent that he’s gone in his career, it was incredible to me we can still have the same kind of conversation.

That energy shows between you in the one-on-one interview in the documentary. How does it feel to be on the other side of that, knowing that you’ve spoken to so many artists over time, or even in this conversation, how does it feel for you to be the focal point of an interview?

For me being interviewed is always awkward, but to be interviewed for a subject that has something to do with me, like, you know, my life and Video Music Box is even worse. And then it’s difficult to sit and listen to people’s questions if they don’t know about me. For Nas, he knows everything about me. He knows things that I forgot about cause he was a kid. So I had a big impression on him. I think that’s what made it easy for me to sit and talk to Nas because you know, there was no motive behind it. I didn’t feel like somebody was trying to find something out but it was purely from a cultural standpoint.

In the beginning of Video Music Box, you didn’t have the intent on being a personality, a celebrity on camera, any of that, but you eventually made it on screen. I know that there’s a transition period to that and it makes you more public. How did you adapt to that?

Adapting to the camera is not easy. I come from a place where I was a DJ and I worked in clubs. I just let the music do it, you know? So I really was just taking what I was doing and putting it on screen and I just didn’t want to be seen at all. But when the cameras started rolling and it was a little awkward at first. I still walk around New York, like a regular New Yorker, with no security and you know, I want to be free. I want to be able to touch people.

To that point, in the documentary, hip-hop figures speak to you as a comforting personality and how you adapted the Uncle Ralph persona. How were you able to make complete strangers or people that you’re meeting for the first time have comfort and make it resonate in the on-camera product?

Yeah, that’s the funny part, right? When I’m in the club in the beginning and we’re doing shout-outs and I don’t even know these people. I think that’s the thing about the spirituality of Hip Hop. When we somehow connect with each other and we don’t even know each other, but in that moment we are with each other.

In the documentary, we see that you were attracted to TV by your uncle who did James Bond movies. You were attracted to music by shows like American Bandstand and Soul Train, but nobody thought Hip Hop would last. What made you decide to buy into that at the early stage and just basically push everything in?

It was me really seeing the impact that Russell Simmons had on the music industry. How Russell Simmons and I grew up not too far from each other when I moved to Queens. I went with him to a record company one day and I saw how he was accepted. People loved what he did and it was all about the music. I was like, wow this is pretty interesting. From there I knew that there was something that was special about Hip Hop. I’m a little bit older than the beginning of Hip Hop. When he started in his pocket, he was probably two years younger than me. So, I was aware of it, but it wasn’t until I saw what Russell was doing that I was like, man, this thing is really, really taken off.

Today you can use YouTube, cameras are more accessible, social media is prevalent. How did you find the specific people to get in contact to make this an actual thing? And how did you obtain the resources and the access to everywhere that you were?

When I graduated from college and was moving around, I was a cameraman. They told us, look, if you want to use the camera on the weekends, you can use it. I was like, really? So we had accessibility to this equipment and we didn’t know what to do with it, you know? That’s how we started going through these different spots and recording Hip Hop artists. Not just Hip Hop, but R&B, whatever it was that was popping in New York at the time. I grew up in Brooklyn, a heavy Caribbean community so I was following the reggae artists and the silk artists and whatever was going on. That’s how we got access to get these things on TV. We were just shooting it and then started messing around with the editing and we thought hey, this should be a show. And that’s how it started.

It’s another point in the documentary where people would be where you were. So let’s say if there was a show on a Wednesday, you spoke and you hung out, you interviewed, you caught what was going on and then they’ll turn around and it’s available for them to watch on Friday, Saturday. But the people weren’t there to see you behind the scenes of preparing the show, what were those days like?

That was hectic because I could shoot on a Friday and I had to get that out, like right away, because it was still, you know, fresh in people’s minds and so that we can beat anybody else to it. It wasn’t like now, like YouTube on instantly on Instagram. So people are like how is it possible that they have this on TV already? Like three days later. Everybody wants to be first. We wanted to beat whether it was at a party or if I had a new Nas video.

You are a Hip-Hop journalism pioneer. Looking back at it, did you see it that way, that you would be a leading person in this form of media?

I think so. I remember when there was a black person or Latino person that on TV, you would like, oh, I’m happy because of somebody that looks like me. So you paid attention to everything that they did because they must be really good. I came in the steps of Don Cornelius’s and how people of that stature presented themselves so I knew what it would be.

For someone who’s watching this documentary and what’s the most dominant piece that you want them to walk away with?

I think the most dominant piece that I wouldn’t want them to get walk away with is to just be true to the culture and be true to yourself. Be mindful of who’s watching and understand that whatever you’re putting on the TV or whatever on the screen or streaming or whatever it is, other people have to like it. I was really just presenting the other people, I kind of stayed out of the way. I didn’t want to disrupt the communication between the message and the people.

Learn how you can watch You’re Watching Video Music Box via Showtime.

The post Exclusive: Ralph McDaniels Reflects on the Creation of ‘Video Music Box’ appeared first on The Source.